No Need To Pinkify Technology Subjects For Girls

It’s time to avoid using female-friendly stereotypes in order to encourage girls into enjoying Information and Communications Technology (ICT) or computing concepts.

Computer science within UK schools is in an interesting position right now. In addition to the debate about its suitability for the wide interest and ability ranges across UK students is the observation that girls are woefully under-represented.

Girls Taking Computing and ICT Related GCSEs

The statistics are damning – Computing and ICT related GCSEs are taken by only 1.5% of female students, compared to 3.7% for males.

Only 9.8% of students pursuing a Computing A Level course were girls last year.

There have been attempts to redress this imbalance with a ‘pinkifying’ approach to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) subjects, to make something such as coding more attractive to girls.

In a nutshell, this means printing documents on pink and purple polka-dot paper. Creating fonts that are pink and flowery. Purple websites.

A simple Google image search for “Coding for Girls” shows the pinkification of promotional material to encourage girls into computer programming subjects. Lots of pinks and purples, no reference to gaming and not a robot in sight.

Compare the Google Coding for Girls image search to the Google Coding for Boys image search below…

No pinkified colour schemes, lots of references to games and robots.

As the father and teacher of three primary school children, two of whom are girls, I have the weekly pleasure of teaching my daughters to code. I’ve taught in all-boys schools, allgirls schools, co-ed schools, and international schools. The subjects have ranged from Information Technology (IT), ICT and Computing.

Yet at no point did it occur to me that pushing pink, girly stereotypes was essential to recruit more girls into my subject. It is true that boys tend to pick such subjects more than girls, and there are a whole host of reasons why this might be, including gender stereotypes from society at large.

However, to combat the stereotype that boys are just into tech with the stereotype that girls just want flowery pink items is to completely miss the point.

Encouraging Girls Who Code

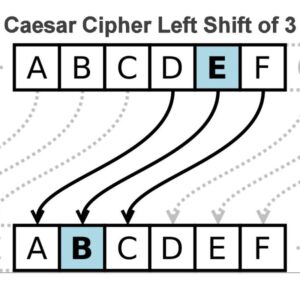

Girls respond to positive role models within society and within schools, to challenging concepts, to having their eyes opened to the sort of STEM concepts that can spring from a KS2 or KS3 lesson, such as a discussion about cyber security or Artificial Intelligence (AI) in self-driving cars. Funnily enough, so do boys.

I teach a wide age range, so I experience what it’s like to teach children in their formative years, as well as when they’re figuring out what adolescence means.

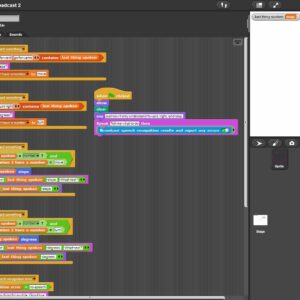

If you pop into one of my classes, you’ll see girls coding HTML and CSS in Year 4.

You’ll see them utilising the principles of Brackets, Indices, Division, Multiplication, Addition, and Subtraction (BIDMAS) in Python programming in Year 9.

You’ll see a lively Google Classroom debate about the ethics of self-driving AI entities in military combat situations.

It didn’t occur to me to encourage the girls to create a website about My Little Pony to hook them into my subject, any more than I’d encourage the boys to focus more on Star Wars or Fortnite.

My daughter in Year 4 is obsessed with puppies, but the website she created recently was about The Clone Wars cartoon series based on Star Wars.

My son in Year 6 still happily watches Waffle the Dog with his younger sisters. His recent Scratch game involved a boss-level character of a pony with love-heart laser beam eyes as a weapon.

One of my star Year 9 students has recently been coming into my computer lab at lunchtime to work on her Python adventure game. In the majority of scenes, you meet a grisly end at the hands of space monsters and haunted beings. Not a hint of pink.

- If I was to heavily encourage the females in my class to use more ‘girly’ concepts or topics, what does that communicate?

- That gender stereotypes are fine as long as girls take up my subject at GCSE?

- That boys should avoid female stereotypes, because there’s no place on an Engineering course at university for boys who code ponies with laser beam eyes?

- Why would I want to perpetuate such ridiculous myths in an age where many schools are seeking to be more inclusive?

Avoiding Gender Stereotypes in the Classroom

All colours and gender preferences should be welcomed. To that end, I try not to introduce male or female stereotyped concepts if I’m setting a project.

Only a couple of years ago, IBM put out a call to women in science and technology to ‘hack a hairdryer’. The aim was to encourage young females into tech. Because clearly hacking a hairdryer would be more interesting and, er, relevant to them than something more boyish. Such as, um, car engines or space flight. IBM is the company behind Watson, and I wish they’d consulted their own vast AI technology to see what Watson would have recommended.

Equally, if girls decide that they want to write pseudocode for baking something quite complicated, because they like The Great British Bake Off, why should that be a problem? It should be no more of a problem than if boys take the same topic.

As educators, we should avoid pushing one activity to one particular gender because we think it will hook them, when all it might do is reinforce the old stereotypes that got us here in the first place.

My aim is to guide the children I teach and father towards a world that’s free from gender stereotypes because they are the generation that will have the power to change these outmoded concepts.

Stephen Trask has worked in a variety of technology-related senior leadership roles in places as diverse as Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Abu Dhabi and West Sussex. He’s currently overseeing technology and data in the New School, Rome, Italy, and he teaches Computing from Year 1 to Year 11.

Originally published in Hello World Issue 5 : The Computing and Digital Making Magazine for Educators. Above article includes modifications from the original article by Stephen Trask. License CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Start a Code Club in Your School @CodeClub #Coding #Teachers #School...

Installing Arduino Device Drivers #Arduino...

Raspberry Pi Camera Module V2 Attached to a Raspberry Pi 3 Model B+ #RaspberryPi...

Arduino IDE Get Board Information #Arduino...

Raspberry Pi Zero Micro USB 2.0 Port #RaspberryPi...

Google Blockly Games Maze 8 Solution #Blockly #Javascript #Coding...